Neurodegeneration and Neuroscience

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common late-onset age-dependent neurodegenerative disease, affecting ~7 million individuals in the United States. Since aging is a critical risk factor driving AD progression, the number of people living with Alzheimer's in the US is expected to double by 2050 with an aging population.

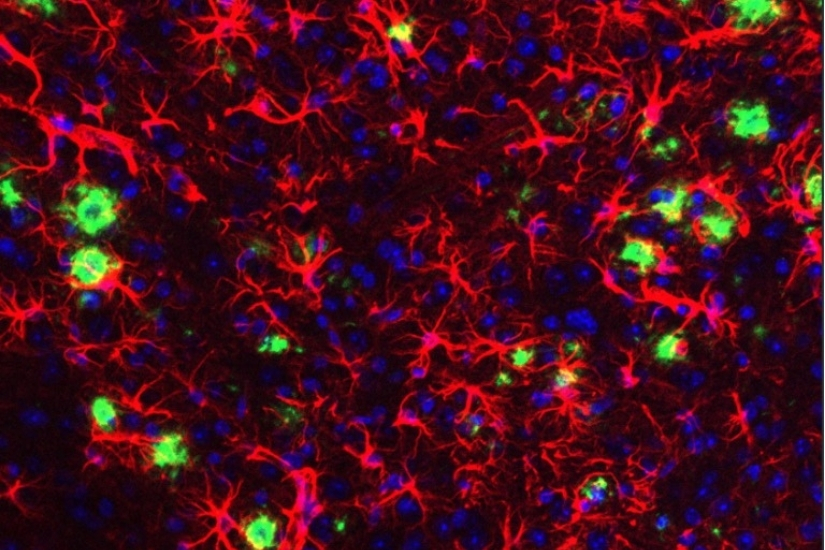

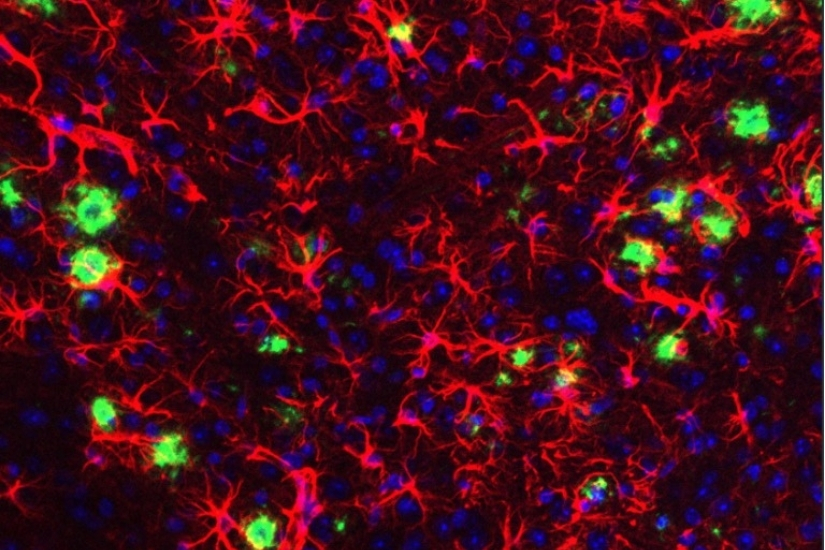

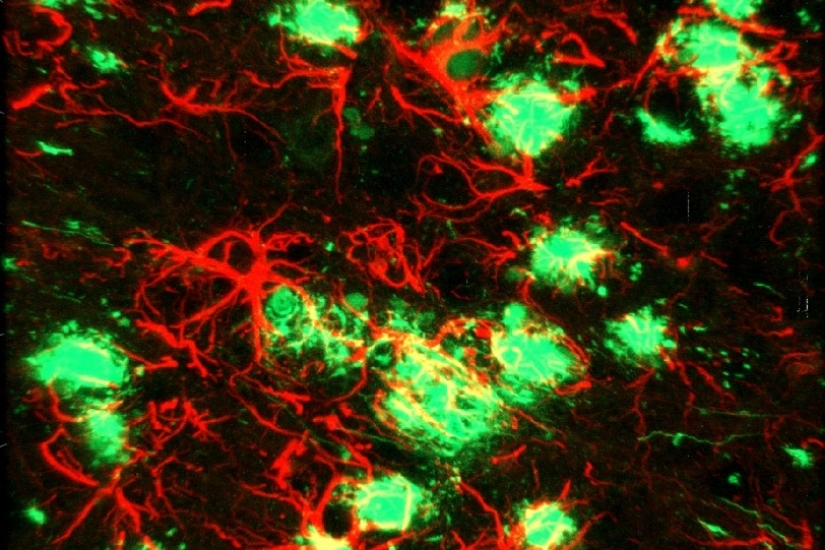

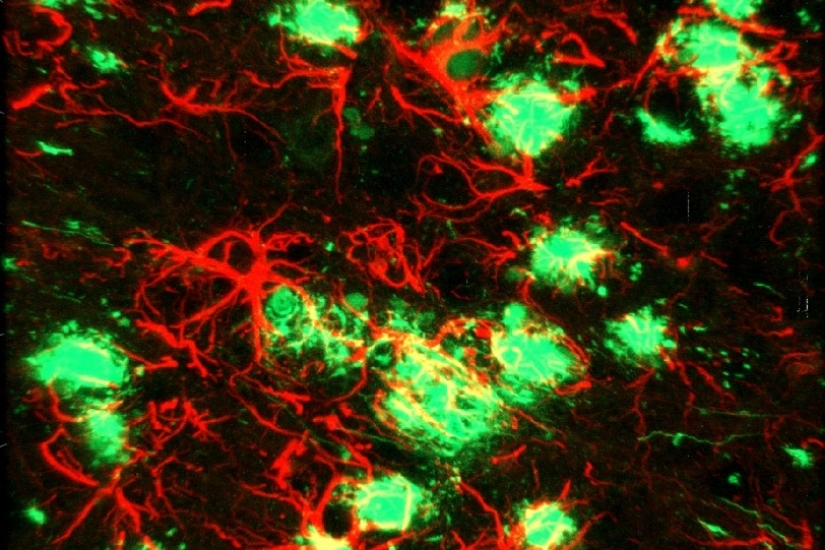

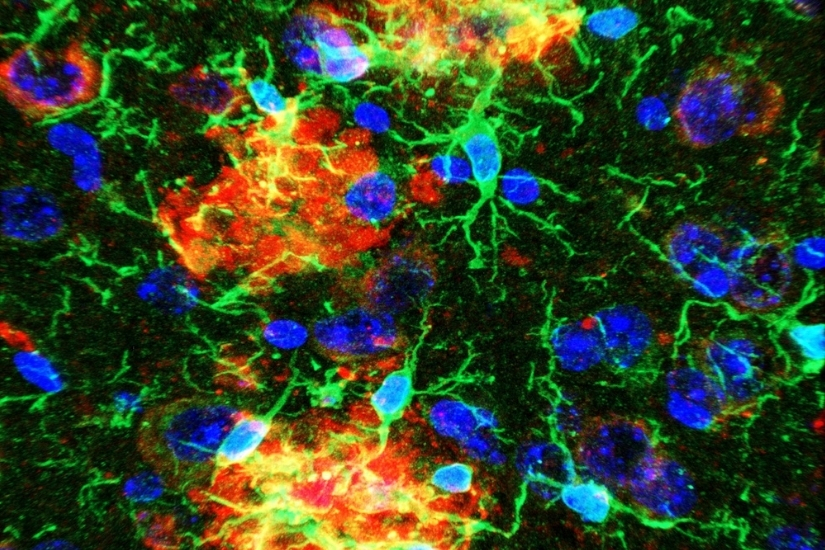

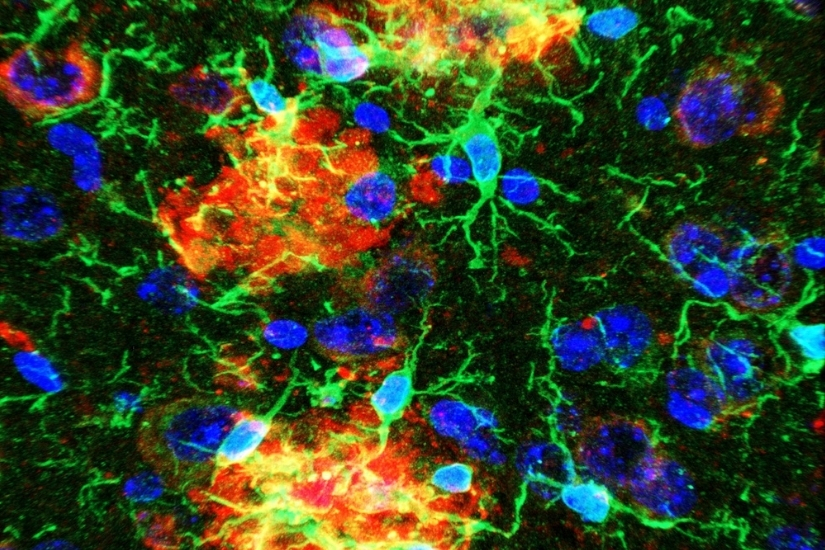

The hallmark pathology found in human AD patient brains is the presence of extracellular deposition of amyloid plaques and aggregates of abnormal protein (tau tangles) in specific subsets of neurons associated with learning and memory. Growing evidence suggests that neurodegeneration in AD is attributed to an initial abnormal generation and accumulation of neurotoxic amyloid beta (Aβ) peptide, which is normally cleared by immune cells in the brain, preventing amyloid buildup. Thus, most therapeutic strategies have evolved around either reducing Aβ generation or boosting the immune response aimed at effective Aβ clearance.

Genome-wide association studies on human brains derived from AD and healthy subjects

have identified several risk genes concentrated in microglia that are directly or

indirectly associated with amyloid phagocytosis and clearance. Thus, the current focus

has shifted to understanding the role of these microglial genes in disease progression.

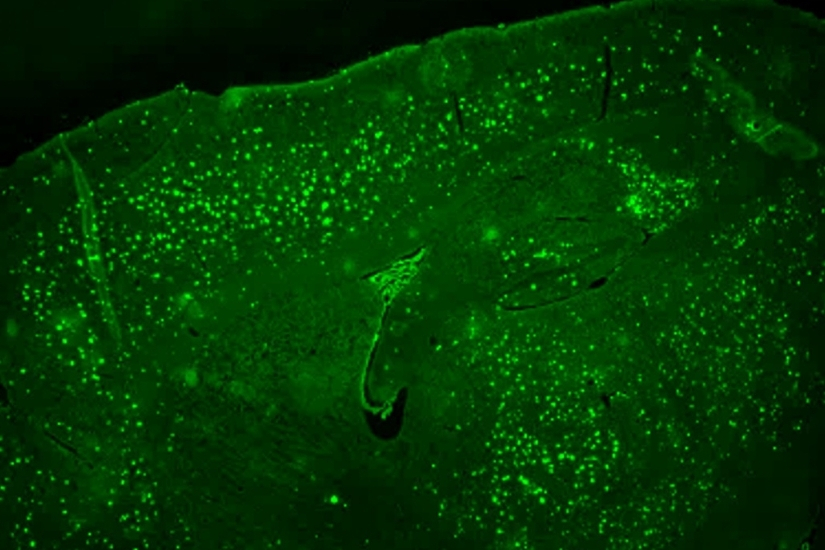

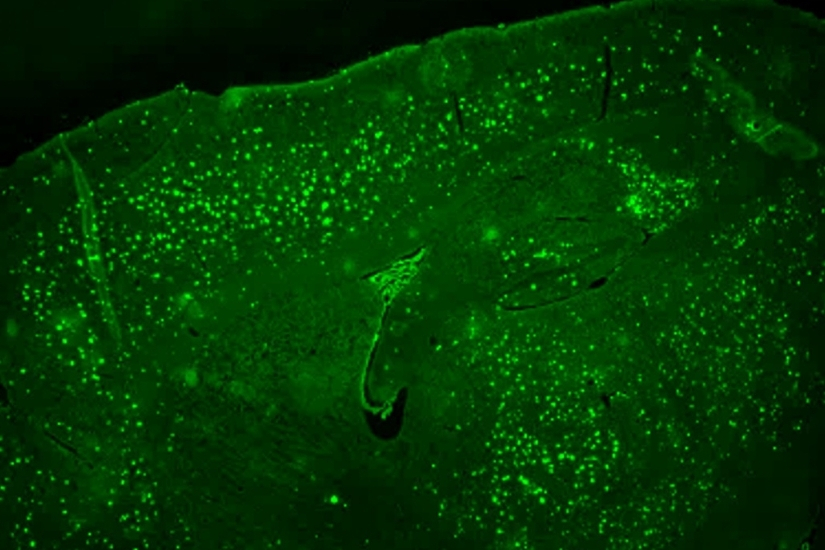

By utilizing state-of-the-art bioinformatics on transgenic AD mouse models and various

conditional knockout mice models targeting transcriptional factors (TF), Department

of Physiological Sciences Principal Investigators are deciphering the role of these

TFs in regulating microglial functions and identifying the downstream genes as potential

therapeutic targets in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.